Key Figures

The Seven Signatories of the Proclamation of Independence

The seven members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) Military Council who planned the Rising, served as signatories of the Proclamation of Independence, and who were all executed by the British Government after the Rising, were:

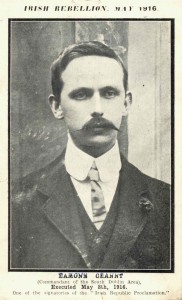

Eamonn Ceannt

Eamonn Ceannt, the son of a Royal Irish Constabulary (police) officer, was born in 1881 in the police barracks at Ballymoe, County Galway. His birth name was Edward Thomas Kent.

- Eamonn Ceant

Credit: Dublin City Library & Archive

Taught by Christian Brothers, he was a devout Catholic. His family moved to Dublin upon his father’s retirement. Ceannt later attended University College, Dublin (UCD). He joined the Gaelic League around 1900. Through that organization, he met Patrick Pearse and Eoin MacNeill.

He then became a fluent in the Irish language and adopted the Irish form of his name. He taught Irish and played a number of musical instruments. This was when he founded the Dublin Pipers’ Club.

He was an accountant in the City Treasurer’s Office, Dublin Corporation. He was involved in the union organizing of workers in Dublin Corporation, where he became chairman of the Dublin Municipal Officers’ Association.

In 1907, he joined the newly formed Sinn Fein political party, which opposed Home Rule and promoted the notion of national self-reliance and worked toward national independence. He was sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in 1912. He helped form the Irish Volunteers in November 1913.

He married Áine O’Brennan. The two had a son Rónán.

Ceannt was in command of roughly 120 men of the 4th Battalion of Irish Volunteers at the South Dublin Union in 1916 during the Rising. The Union was a workhouse/hospital that covered 52 acres next to James’s Street. His battalion held a portion of the site until learning of the surrender on Sunday. That site is now the location of St. James’s Hospital.

A signatory of the Proclamation of Independence and a member of the Provisional Government, on May 8, 1916, he was executed by firing squad.

His widow Áine Ceannt later formed the White Cross to come to the aid of those families devastated by war.

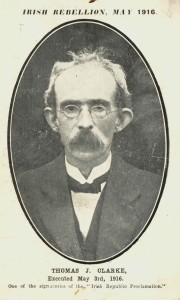

Thomas J. Clarke

Thomas J. Clarke is regarded by many historians as the architect of the 1916 Rising.

- Thomas J. Clarke

Credit: Dublin City Library & Archive

Clarke was born in 1858 on or near the Isle of Wight. His Irish father was a sergeant in the British army. Clarke’s family moved to South Africa and later to Dungannon, County Tyrone, where Clarke was raised.

Due to his involvement with the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), he left Ireland for New York in 1882.

Once there he joined the Republican Clan na Gael. His advocacy for violent revolution and his role in a series of London bombings led to him spending 15 years in British jails.

In 1898 he was released from prison. He returned to America, where he lived for nine years, and married Kathleen Daly. While in the United States, Clarke resumed his revolutionary activities.

He returned to Dublin in 1907 where he became a tobacconist. In Dublin, he joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). It is largely believed that Clarke was a key to the resurgence of the IRB and integral in preparations for Rising.

He was the first signatory of the Proclamation of Independence. He was part of the group that occupied Dublin’s GPO during the Rising. It was said that he opposed the eventual surrender, but was outvoted.

Clarke was executed for his role in the rising on May 3, 1916.

He and his wife Kathleen had three children. Post mortem in 1922, a collection of his prison writings, Glimpses of an Irish Felon’s Prison Life, was published.

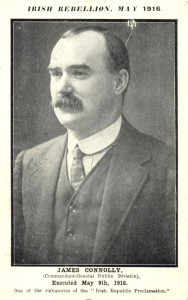

James Connolly

James Connolly was born in 1868 in Edinburgh to parents who were Irish Catholic immigrants. It was reported that Connolly grew up in extreme poverty. He first went to work when he was 11 years old. He joined the British Army when he was 14. He served the army in Ireland for seven years. During that time, he served in Cork, Dublin and the Curragh in Kildare. In 1890 he married Lillie Reynolds.

- James Connolly

Credit: Dublin City Library & Archive

That year, he returned to Edinburgh, where he became active in the socialist politics of the era. Like many of the time, he was self-taught. He read mostly of history, politics, economics and socialism.

Connolly then went back to Ireland and settled in Dublin in 1896, founding the Irish Socialist Republican Party. He published the party’s newspaper The Workers’ Republic. He was an opponent of Home Rule.

In 1903, he travelled to the United States to conduct lectures. The next year, his family joined him in New York, where he had become very active in Irish nationalist circles.

By 1907 Connolly had founded the Irish Socialist Federation. He was editor of its publication called The Harp that he established 1908. During his time in the States, he penned works that became widely known, including Labour in Irish History, and Labour, Nationality and Religion. These were actually published in Dublin in 1910.

In 1912, back in Dublin, Connolly co-founded the Labour Party. This served to unite Catholic and Protestant workers against employers when the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) became involved in bitter labor disputes and strikes. These disputes were marked by the Dublin lock-out of 1913. He had become an organizer in the union, and when its leader James Larkin left for the United States in 1914, Connolly was elevated to run the ITGWU and serve as the editor of the Irish Worker.

This also entailed his serving as commandant of the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), which was formed to protect workers during the 1913 lock-out. Connolly led the Citizen Army and publicly called out the Irish Volunteers for what he alleged was inactivity.

When World War I began in 1914, Connolly started anti-recruitment campaign. In January of 1916 he reached agreement with the leadership of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) for a joint insurrection involving the Irish Volunteers and the ICA. As a result, he joined the IRB and was integral to plans for the 1916 Rising.

On Easter Monday he led his 250-member Citizen Army alongside the Volunteers under Pearse. It was also said that he was a major contributor to the wording of the Proclamation of Independence. He was named vice president of the Provisional Government.

He served as Commandant-General Dublin Brigade of the Army of the Irish Republic in the GPO and was badly wounded on the Thursday of Easter Week, but remained in charge.

Unable to stand because of his serious wounds, Connolly was strapped to a chair and executed by firing squad on May 12, 1916. He was survived by his wife Lillie and children, including his son Rory, who served with him in the GPO.

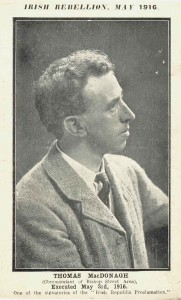

Thomas MacDonagh

Thomas MacDonagh was born in 1878 and was a native of Tipperary. He attended Rockwell College, studying to become a priest. Instead, he became a teacher at St. Kieran’s College in Kilkenny from 1901 to 1903, and then at St. Colman’s College in Cork from 1903 to 1908. It was also during these years that he joined the Gaelic League.

- Thomas MacDonagh

Credit: Dublin City Library & Archive

He worked to become more fluent in the Irish language by traveling to the Aran Islands. There he met Patrick Pearse. Later, when Pearse opened St. Enda’s school in 1908, MacDonagh signed on as assistant head teacher.

MacDonagh taught full time and studied part time at University College, Dublin (UCD), where he earned his bachelor’s degree in 1910. He then earned a master’s degree the next year and was hired on as a lecturer in English at UCD.

In 1909, he helped form the Association of Secondary Teachers of Ireland (ASTI), and in 1911 he helped organize the Irish Women’s Franchise League (IWFL). For a period, he was editor of Irish Review. The IWFL promoted Irish nationalism. MacDonagh was known as a talented poet and writer. His play “When the Dawn is Come” was produced at the Abbey Theatre.

In 1913, he was a member of the Dublin Industrial Peace Committee during the labor lock-out. That same year, he joined the Irish Volunteers.

He joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in April 1915. He did not have a significant amount of input into the planning of the Rising, but it is thought that he was a contributor to the shaping of the Proclamation of Independence.

MacDonagh was one of the four Dublin battalion commandants, during the Rising overseeing the 2nd Battalion of the Irish Volunteers at Jacob’s biscuit factory on Bishop Street in Dublin. That factory did not come under direct assault.

He was executed on May 3, 1916 and was survived by his wife Muriel Gifford and his children Donagh and Barbara.

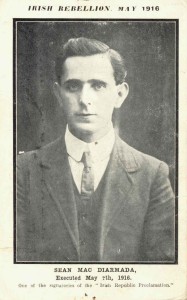

Sean McDermott (Seán Mac Diarmada)

Sean Mac Diarmada was born in 1883 in Leitrim. He moved to Glasgow in 1900 where became as a tram conductor. He then returned to Belfast in 1902, where he was a member of the Gaelic Athletic Association and the Gaelic League. He had joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and then transferred to Dublin in 1908, where he managed the IRB newspaper Irish Freedom in 1910.

- Sean McDermott

Credit: Dublin City Library & Archive

Mac Diarmada contracted the polio virus in 1911 and subsequently required a cane. He and Tom Clarke, and others were given credit for the resurgence of the IRB.

Once World War I had begun in 1914, Mac Diarmada started a campaign to discourage Irish men from joining the British army. For that, he was jailed under the Defence of the Realm Act.

He became an outspoken promoter of violent revolution for Ireland’s independence. In one speech at Tralee, County Kerry he told the crowd, “The Irish patriotic spirit will die forever unless a blood sacrifice is made in the next few years.”

He had a reputation for secrecy, even to the extent that he reportedly excluded several of his fellow IRB members from the planning of the 1916 Rising. He has been described by historians as the driver behind that planning process. This obsession with secrecy and exclusion was blamed for some of the confusion surrounding implementation of the Rising.

During the Rising he was in the GPO, which is where most of the members of the Provisional Government were located. Unmarried, he was executed on May 12, 1916.

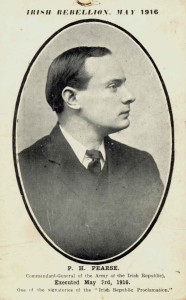

Padraig (Patrick) Pearse

Padraig Pearse was born in 1879 in Dublin on Great Brunswick Street, which is now Pearse Street. He studied at University College, Dublin (UCD), and later studied law at Trinity College, Dublin and the King’s Inns.

- Padraig Pearse

Credit: Dublin City Library & Archive

He joined the Gaelic League in 1895 and was editor of its newspaper. In 1898 he became a member of its Executive Committee.

Pearse taught Irish part time in various schools and at UCD. In 1908, he created a bilingual school for boys, S.t Enda’s, in Dublin.

According to historical accounts, Pearse was originally a supporter of Home Rule but this changed when he played a role in the formation of the Irish Volunteers in November 1913.

By July 1914, Pearse had become involved in smuggling weapons and ammunition that he stored at St. Enda’s. In December of that year he was sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

His passions for Irish independence became so strong that his graveside oration at the funeral of Fenian leader O’Donovan Rossa became a rallying cry for those ready and willing to fight for that independence. His oration on August 1, 2015 ended with the much quoted words “Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.”

In September 1915 he was elected to the Supreme Council of the IRB and joined the military council.

Pearse was the author of the Proclamation of Independence. He was in the GPO during the Rising, and was Commander in Chief of the Irish forces. He was nominated by his fellow signatories to be President of the Provisional Government. He was the one to read the Proclamation outside of the GPO on Easter Monday.

It was Pearse, who at 3.30 p.m. on April 29, 1916 who surrendered unconditionally on behalf of the Volunteers to Brigadier-General W. H. M. Lowe in Parnell Street. The decision was made democratically among the Volunteers in order to prevent further loss of civilian life.

Pearse held a crucifix when he was executed by firing squad on May 3, 1916. He was unmarried.

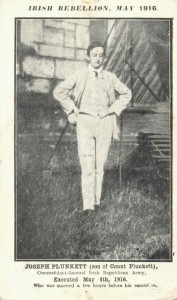

Joseph Plunkett

Joseph Mary Plunkett was born in Dublin in 1887. He was educated at the Catholic University School, Belvedere College and Stonyhurst College in Lancashire, England. He became an avid writer of poetry.

- Joseph Plunkett

Credit: Dublin City Library & Archive

Plunkett’s interest in poetry, along with religion and mysticism were interests he had in common with Thomas MacDonagh who tutored him in preparation to attend college. Plunkett and MacDonagh became close friends.

Plunkett graduated from University College, Dublin (UCD) in 1909. Shortly after that, he came down with tuberculosis and travelled to Italy, Algeria and Egypt from 1910 to 1912.

Meanwhile, MacDonagh created a literary journal called Irish Review in 1911 and published some of Plunkett’s poetry. Plunkett then became an editor of the publication. After that, Irish Review became more political, supporting Sinn Féin on issues of the day, most notably labor matters and the 1913 lock-out.

Both MacDonagh and Plunkett would join with Edward Martyn to create the Irish Theatre in November 1914.

In 1913, Plunkett was elected to the provisional committee of the Irish Volunteers. He then joined the IRB. In 1915 he travelled to Germany to help Sir Roger Casement procure arms and support for the 1916 rising.

Historians have said that Plunkett and Mac Diarmada were responsible for forging a missive dated April 19, 1916 that was characterized as coming from Dublin Castle. The document inferred that authorities were about to more aggressively suppress the Irish Volunteers. The obvious intent for such a tactic would be to embolden the Irish Volunteers and prepare them for action. Authorship of the document has never been confirmed.

Plunkett helped devise the military strategy for the Rising and was the youngest of the seven to sign the Proclamation. Reports were that at the time of the rising, Plunkett was recovering from surgery to his glands and was in poor health.

After the Rising, on the night before he was to be executed, he married Grace Gifford, who was sister-in-law to Thomas MacDonagh. He faced the firing squad, on May 4, 1916.